Main content blocks

Section outline

-

-

Բարև Ձեզ։ Ես Նաիրա Հրայրյանն եմ։ Ծնվել և մեծացել եմ Երևանում 1977 թվականին, մեծ հայրենասերի՝ Մայիս Հրայրյանի ընտանիքում։

Երբ փոքր էի, կարդալ շատ էի սիրում։ Մենք մեծ գրադարան ունեինք։ Երբ սկսեցի քիչ թե շատ հասկանալ և հետաքրքրվել մեր ազգի պատմությամբ, արդեն 1980-1990 թվականն էր։ Ազատագրական շարժումը սկսել էր գլուխ բարձրացնել։ Մի անգամ, երբ Եղեռնի մասին էինք զրուցում ես, հայրս, քույրս, հայրս ասաց․

-Էլ վտանգավոր չէ լինել մեծ ֆիդայապետի ծոռնիկ, արդեն ավելի քան պարտավորեցնող է արժանի լինել մեծ հայի ժառանգը։ Ես ուզում եմ ձեզ պատմել մեր մեծ ազգից փրկված միակ երեխայի՝ Բաբկեն պապիկի ճակատագրի մասին։ Մեր Բաբկեն պապը Լենինականի որբանոցից է եղել, այնտեղ էլ ծանոթացել է տատիկիս հետ, ում ծնողները Ղարսից են եղել և կոտորվել են։

Բաբկենը, երբ անձնագիր է ստանում, որոշում է դառնալ Հրայրյան, որովհետև նա հայոց համազգային շարժման ղեկավարներից մեկի՝ Արմենակ Տեր-Ղազարյանի (Հրայր Դժոխքի) մեծ գերդաստանից փրկված միակ երեխան է եղել։ Ազգանունը փոխելուց հետո նա ամբողջ կյանքում հետապնդվում և հաճախ աքսորվում է։ Նույնիսկ բանտարկվել է ֆիդայապետի ազգական լինելու համար։ Նրա երեխաները՝ Պետիկը, Լիդան, Զինան, Լյովան և Մայիսը մեծացել են անհայր, որովհետև նրան միշտ հետապնդել և աքսորել են։ Ուզում եմ ձեզ պատմել Բաբկեն Տեր-Ղազարյանի փրկության և Հրայրյան գերդաստանի վերածննդի պատմությունը։ Բաբկենը պատմել է, որ մեծացել է մի մեծ բակում իր հոր և հորեղբայրների ընտանիքների հետ, նրա պատմելով՝ քառասունից ավելի մարդ` մեծ ու փոքր։ Նրա հայրը եղել է գրագետ և զարգացած մարդ, եղել է գյուղի քահանան՝ Մամբրե Տեր-Ղազարյան։ Նրանց ընտանիքը շատ հարուստ է եղել, մեծ տնտեսություն է ունեցել, նույնիսկ քուրդ ծառաներ և նախիրները պահող հոտաղներ։ Մամբրե Տեր-Ղազարյանը շատ հարգված մարդ է եղել։ Նրանք ապրել են Սասունի Խուլբ գավառի Ահարոնք գյուղում, հետո գաղթել են Մշո դաշտ՝ Ղզլաղաջ գյուղ։

Երբ գյուղում խժդժությունները տարածվել են, սկսվել է խուճապը և անորոշությունը։ Քրդերը, որոնք իբրև թե բարեկամ են եղել Մամբրեին և իր եղբայրներին, ասել են․

—Թուրքական կառավարության կողմից բարձրաստիճան զինվորականներ են գալու, որ տարածքը ստուգեն։ Արի՛ դու քո գերդաստանով մտի՛ր գոմ, դուռը փակենք, իբրև թե սպանել ենք։ Կգան, կգնան, մենք մարագի դուռը կբացենք։ Ամեն ինչ լավ կլինի։

Մամբրեն խելացի և հեռատես լինելով՝ հասկացել է, որ քրդերի խոսքը վերջինը չէ, չէ որ քրդերը գործիք էին թուրքական կառավարության ձեռքում։

Երբ նրանց ընտանիքին՝ մեծ ու փոքր, գրկի երեխաներին ու հարսներին, քառասունից ավել մարդ փակում են մեծ մարագում և երկու օր նրանց կանչերին ոչ ոք չի արձագանքում, Մամբրեն հասկանում է, որ կճուճ ոսկին չի օգնելու, որ իրենց ընտանիքին չսպանեն (նա մի կճուճ ոսկի է տվել քրդերին), նա հասկանում է, որ պետք է մի բան ձեռնարկի, նայում է մարագի օդանցքին, որտեղից կարող էր դուրս գալ մենակ Բաբկենը, ով 5 տարեկան էր, մնացածը կա՛մ մեծ էին, կա՛մ փոքր։ Բաբկենին օդանցքից հանելուց առաջ հայրն ասում է․

-Բաբկեն ջան, մեզ հաստատ բաց են թողնելու, բայց դու օդանցքից դուրս արի, զգույշ, որ չնկատեն, գնա դիմացի խիտ թփերի մեջ թաքնվիր ու սպասիր, որովհետև այստեղ օդ չկա։ Երբ տեսնես, որ դուռը բացում են կգաս, եթե ուրիշ բան պատահի, փախիր, առանց ետ նայելու փախիր, երբեք չմոռանաս, որդիս, որ դու հայ ես, Աստված քեզ հետ և մեզ պահապան։

Պապիս պատմությունը այնքան հստակ էր շարադրված, որովհետև նա՝ լարելով իր հիշողությունը, գրառում էր դեպքեր, խոսակցություններ, և պատմություններ իր գաղթի ճանապարհից, որպեսզի գիրք գրեր իր պահված կյանքի մասին։

Բաբկենի պատմելով՝ բլրին, թփերի տակ թաքնված մենակ տեսնում է, որ քրդերը մարագը այրում են, ճիչ, աղաղակ, լացուկոծ, նա, հասկանալով, որ պետք է վազի ու գնա, սկսում է փախչել։ Քրդերը նկատում են, ետևից կրակում։ Գնդակը չի կպնում իրեն, բայց Բաբկենը քարաժայռը մագլցելիս գլորվում է, ընկնում, ուշագնաց լինում։

Քրդերը կարծում են, որ սպանեցին և հեռանում են։ Բաբկենը ուշքի է գալիս, ետ գնում իր տուն, թաքուն մտնում բակ, որտեղ արդեն ապրում էին իրենց ծառայող քրդերը։ Քրդի հարսները նկատում են Բաբկենին, որին շատ էին սիրում, և քանի որ նրանց սկեսրայրը և ամուսինները տանը չեն լինում, գնացած են լինում կողքի գյուղերը ավար բերելու, Բաբկենին լողացնում են, կերակրում, քնեցնում։ Առավոտյան ասում են ոչխարները տար արածեցնելու։

Մի քանի օր Բաբկենը մնում է տանը, օգնում է հարսներին։ Նրան թաքցնում են հարևան թուրքերից, ասում են, որ չեն վնասելու։ Մի քանի օրից, երբ վերադառնում են քուրդ աղան ու որդիները, քրդուհին մի խուրջին հաց ու ուտելիք է տալիս Բաբկենի շալակը, պատուհանից հանում՝ ասելով․ «Բաբկեն ջան, փախի՛ր, վազի՛ր, մինչև հայերի քարավան գտնես»։ Եվ Բաբկենը, լինելով հինգ տարեկան, միայնակ, քարերով, սարերով մի խումբ փախստական հայերի գտնելով, մի կերպ հասնում է Լենինականի (այժմ՝ Գյումրի) որբանոց, որտեղ հայտնվել էր նաև պապիկս, իր քույրիկի հետ։ Հետագայում նա ամուսնանում է և ունենում հինգ երեխա։

Մեծ տարիքում պապիկս որոշում է գիրք գրել, հայրս պատմում էր, որ տեսել է գրքի ցանկը, ձեռագիր, որը հետո ինչ-ինչ պատճառներով կորել է աքսորի ճանապարհին։

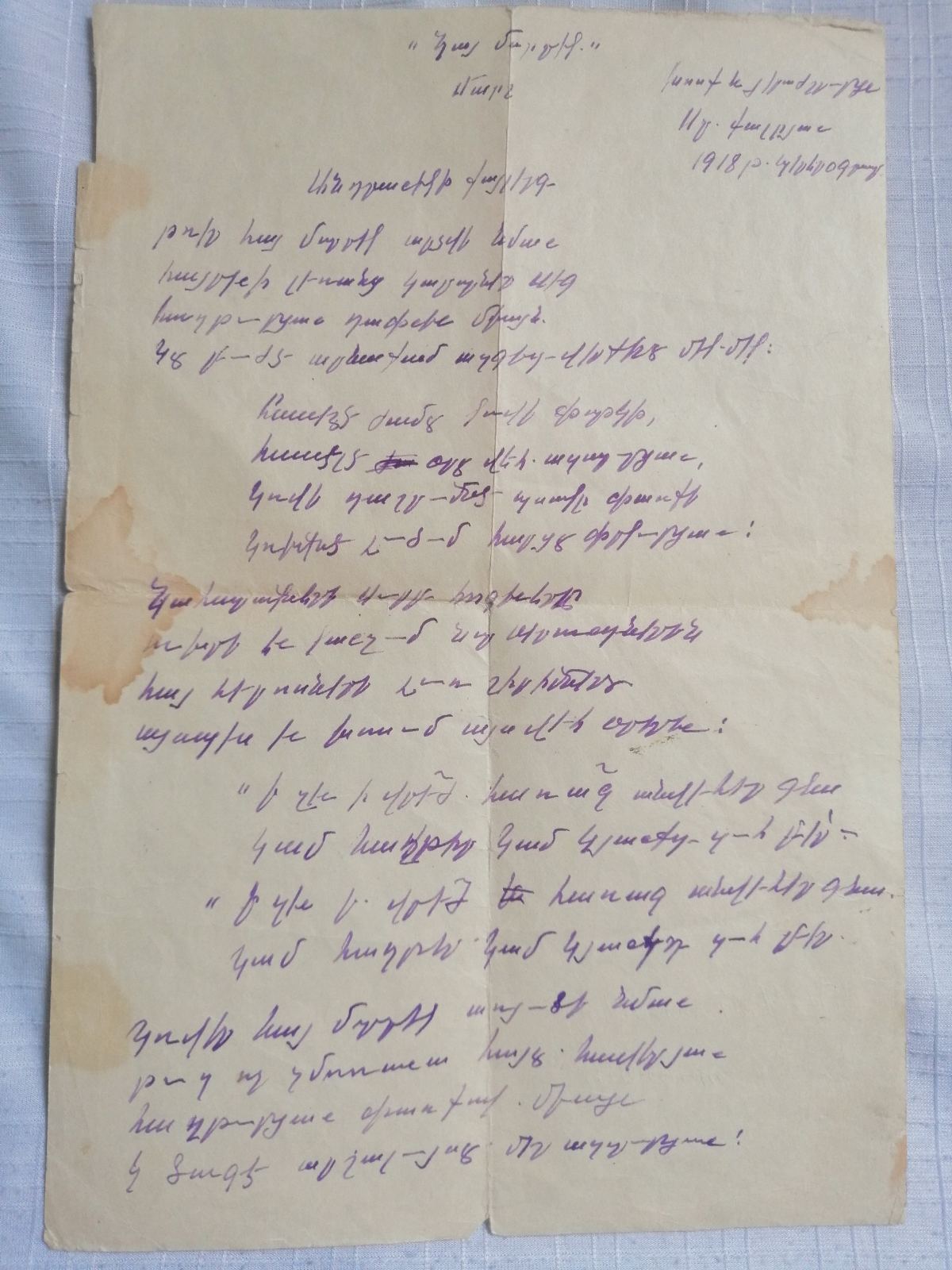

Պապիկիցս ինձ մնացել է մի ձեռագիր, արի վրա գրված է «Երգ Անդրանիկի մասին», իսկ հակառակ կողմում գրված է ամիս, ամսաթիվ և «խոշորագույն կապիտալ»։ Այն ինձ համար այսօր իրոք շատ մեծ արժեք ունի։

Պատանեկության տարիներին ես շատ գրքեր և հոդվածներ եմ կարդացել Եղեռնի մասին, Հրայր Դժոխքի մասին, նրա անցած ուղու, նրա հայրենանվեր աշխատանքի, թե ինչպես թաքուն, գիշերով գյուղից գյուղ է անցել, մարդկանց հավաքագրել, զենք բռնել և ինքնապաշտպանվել սովորեցրել և քարոզել «մահ կամ ազատություն»։ Նրանից շատ են վախեցել քրդերն ու թուրքերը և նրան՝ Արմենակ Տեր-Ղազարյանին, Հրայր Դժոխք են անվանել, նույնիսկ դավաճաններն են վախեցել նրան մատնել։ Ես շատ տեղեկություններ, հոդվածներ և քարտեզներ էի հավաքել Հրայրի մասին։ Մի անգամ մեր տուն եկավ պատմաբան Աշոտ Ներսիսյանը, իմ հորեղբոր տղայի՝ Բաբկենի հետ, և ասաց, որ գիրք է գրելու Հրայրի մասին և ես իմ ողջ ունեցած տեղեկությունները տվեցի նրան։ Եվս մի ուշագրավ բան նշեմ․ հետագայում Բաբկենի երեք տղաներից միայն Պետիկը տղա ունեցավ, նրան անվանեցին Բաբկեն, իսկ Բաբկենի որդին՝ Հրայր Հրայրյանը դարձավ Տեր-Ղազարյան գերդաստանը շարունակող թանկ ժառանգը։ Հիշում եմ հայրս Բաբկենին՝ իր եղբոր որդուն, շատ էր սիրում, իսկ Հրայրը նրա համար մի ուրիշ աշխարհ էր։

Շնորհակալ եմ ՀԲԸՄ-ին և Հայկական վիրտուալ համալսարանին, որ կազմակերպել է ոգեկոչման առանձնահատուկ միջոցառում՝ լուսարձակի տակ առնելու վերապրողների կյանքի պատմությունները։

Ավարտելով պապիկիս փրկության պատմությունը՝ ասեմ, որ իմ Պետիկ հորեղբոր տղա Բաբկենի որդին՝ Հրայր Հրայրյանը, և պատմաբան Աշոտ Ներսիսյանը և Հ1 հեռուստաալիքի օպերատորները գնացել են կատարելու իմ հոր՝ Մայիս Հրայրյանի նվիրական անկատար երազանքը։

Գնացին գտնելու Հրայրի տունը, գյուղը, գերեզմանը։ Այս ամենն ավելի հանգամանալից կա Հրայր Դժոխքի մասին պատմավավերագրական ֆիլմում։

Շնորհակալ եմ Մարինե Խաչատուրյանին աջակցության համար։

English text

Hello,

Allow me to introduce myself. I am Naira Hrayryan, born and raised in Yerevan in 1977, into the family of Mayis Hrayryan, a devoted patriot.

During my childhood, I developed a deep love for reading, nurtured by our extensive family library. As I grew older and became more interested in the history of our nation, it was the late 1980s and early 1990s, a time when the liberation movement was gaining momentum. In one poignant conversation about the Yeghern (the Armenian Genocide) with my father and sister, my father shared a profound insight:

"It is no longer merely an honor to be the great-grandchild of a courageous fidayi[1]; it has become our solemn duty to carry forward the legacy of being descendants of a great Armenian."

I want to recount the story of my grandfather, Babken, the sole surviving child of our remarkable nation. Grandfather Babken hailed from the Leninakan orphanage, where he met my grandmother, a woman whose parents hailed from Kars and tragically fell victim to the massacres of that time.

When Babken acquired a passport, he made a pivotal decision to adopt the surname Hrayryan, honoring his lineage as the sole surviving child of Armenak Ter-Ghazaryan, one of the prominent leaders of the Armenian national movement, known as Hrayr Djokhk[2]. This choice, however, marked him for a lifetime of persecution and frequent exile due to his association with the fidayi movement. As a consequence, his children - Petik, Lida, Zina, Lyova, and Mayis - grew up without their father's presence, as he was perpetually on the run from those who sought to harm him.

Allow me to share with you the remarkable story of Babken Ter-Ghazaryan's survival and the resurgence of the Hrayryan legacy.

Babken reminisced about his upbringing within a sprawling courtyard that housed not only his immediate family but also the families of his father and uncles, totaling more than forty individuals of all ages. His father, Mambre Ter-Ghazaryan, was an educated and enlightened individual, serving as the village priest. Their family was affluent, managing a vast estate complete with Kurdish servants and shepherds. Mambre Ter-Ghazaryan commanded immense respect within the community. Initially residing in the village of Aharonk in the Khulb province of Sassoon, they later migrated to the village of Ghzlaghaj in the field Mush.

As tensions escalated within the village, a wave of panic and uncertainty gripped the community. The Kurds, who were ostensibly allies of Mambre and his brothers, offered a solution:

"High-ranking military officials from the Turkish government are expected to inspect the area. Come, take your large dog, and hide in the granary. We'll close the door, making it seem as though a crime has occurred. They will come, conduct their inspection, and leave. Then, we can open the granary door and resume our normal activities. Everything will be fine."

However, Mambre, being astute and forward-thinking, understood that the Kurds' assurance was not definitive. He recognized that the Kurds were mere pawns manipulated by the Turkish government, and their promises could not be entirely trusted.

In the cramped granary, where more than forty members of their family were confined, including the young and the elderly, children, and daughters-in-law, an eerie silence settled in after two days of unanswered calls. In that desperate moment, Mambre came to a sobering realization: no amount of gold could guarantee the safety of their family, even though they had offered a lump of gold to the Kurds. He knew he had to take action.

Surveying the surroundings, Mambre's eyes fell on a vent in the granary, just big enough for five-year-old Babken to slip through. The other children were either too old or too young to fit. Before gently guiding Babken through the vent, Mambre imparted words of wisdom:

"Dear Babken, they will eventually release us, but you must crawl out of this vent carefully, ensuring no one sees you. Find shelter in the dense bushes nearby and wait patiently, for there is no air in here. When you see them opening the door, come to us. However, if anything else occurs, run, run without looking back. Always remember, my son, that you are Armenian. May God be with you and protect us."

My grandfather recounted this story with remarkable clarity, as he diligently preserved his memories and documented incidents, conversations, and tales from his journey, intending to compile them into a book that chronicled the life he had lived through.

According to Babken's account, as he hid alone on the hill beneath the bushes, he witnessed the Kurds setting fire to the granary. Amidst the chaos of screams and cries, he knew he had to escape, prompting him to sprint away. The Kurds, noticing his flight, shot at him from behind. Miraculously, the bullet missed, but while climbing a rock, Babken stumbled, fell, and lost consciousness.

Believing him dead, the Kurds departed. When Babken woke up, he retraced his steps back to his house. Sneaking into the courtyard, he was noticed by the Kurdish daughters-in-law, who held great affection for him. With their fathers-in-law and husbands away, these women ventured to neighboring villages for loot. They cared for Babken, bathing him, feeding him, and tucking him in. The next morning, they asked him to tend to the sheep.

For several days, Babken stayed hidden at home, assisting the women. They shielded him from nearby Turks, assuring him of his safety. After a few days, when the Kurdish chieftain and her sons returned, the woman provided him with bread and food, urging him to escape through the window. "Dear Babken," she said, "run, run until you find the Armenian caravan." Thus, at the tender age of five, alone and determined, Babken navigated through rocky terrains and mountains, eventually encountering a group of Armenian refugees. With sheer determination, he made his way to the Leninakan orphanage (now Gyumri), where he was eventually reunited with his sister. Later in life, he married and had five children.

In his later years, my grandfather embarked on the task of writing a book. My father once mentioned seeing the manuscript, a list of chapters titled "Song of the Inauguration," which, unfortunately, got lost during his exile. My grandfather left behind a precious artifact for me—a manuscript bearing the inscription "Song of the Inauguration" on one side and the date along with the words "huge value" on the reverse. Its value to me today is immeasurable.

During my youth, I delved into numerous books and articles about the Genocide, learning about Hrayr Dzhokhk's courageous path, his patriotic endeavors, and his clandestine missions from village to village at night. He recruited people, imparted self-defense skills, and fervently preached "death or freedom." His reputation struck fear into the hearts of Kurds and Turks alike; even traitors dared not betray him. I meticulously gathered information, articles, and maps about Hrayr.

I vividly recall a moment when the historian Ashot Nersisyan visited our home with my cousin Babken. Ashot expressed his intention to write a book about Hrayr, and I eagerly shared all the information I had collected.

There's another remarkable thread to this story. Among Babken's three sons, only Petik had a son named Babken. Babken's son, Hrayr Hrayryan, became the esteemed heir, continuing the legacy of the Ter-Ghazarian dynasty. My father held a deep affection for Babken, his nephew, and for him, Hrayr represented an entirely different world—a world of reverence and significance.

I express my heartfelt gratitude to AGBU and the Armenian Virtual College for organizing a special commemorative event that shed light on the life stories of the survivors.

Completing the narrative of my grandfather's rescue, it's important to mention the dedicated efforts of Hrayr Hrayryan, the son of my cousin Babken, historian Ashot Nersisyan, and the team from H1 TV channel. They embarked on a poignant journey to fulfill my father Mayis Hrayryan's cherished but unrealized dream—to locate Hrayr's house, village, and grave. These details are intricately woven into the fabric of the documentary film about Hrayr Dzhokhk, a testament to their unwavering dedication and perseverance.

I extend my gratitude to Marine Khachaturyan for her unwavering support throughout this endeavor.

-